Ray Milland as Don Birnam in "The Lost Weekend" (1945) directed by Billy Wilder

"Had the day really gone, had it really managed to pass, he was still sane, still alive? The room was cool, the sunlight had long since left the carpet, though he hadn’t realized it till now. He turned to look out the window. The sun had withdrawn also from the apartment building across the way, it was getting dark. Now what? What about the night, how was he going to survive it?— for he knew that sleep, in this keyed-up state, was beyond possibility. Or was Helen going to arrive and attempt again to rescue him from that night? Never! He would face a nightmare night of devils and creeping horror and shrieking empty bottles twenty times more dreadful than the dreadful day, rather than face Helen, rather than open the door to her. Let her ring the bell, let her ring her head off, he was beyond reach now. He clutched the arms of the chair, fixed his eye on the door, and waited for the bell to ring." -"The Lost Weekend" (1944) by Charles R. Jackson

"Some Halloween jokester had split the side windows of the bus and she shifted back to the Negro section in the rear for fear the glass might fall out. Two nurses she knew were waiting in the hall of Mrs Hixson's Agency. 'What kind of case have you been on?' 'Alcoholic,' she said. 'Gretta Hawks told me about it--you were on with that cartoonist who lives at the Forest Park Inn.' The phone rang in a continuous chime. [...] He was looking at the corner where he had thrown the bottle the night before. She stared at his handsome face, weak and defiant--afraid to turn even half-way because she knew that death was in that corner where he was looking. She knew death--she had heard it, smelt its unmistakable odour, but she had never seen it before it entered into anyone, and she knew this man saw it in the corner of his bathroom; that it was standing there looking at him while he spat from a feeble cough and rubbed the result into the braid of his trousers. It shone there crackling for a moment as evidence of the last gesture he ever made." -"An Alcoholic Case" (1937) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

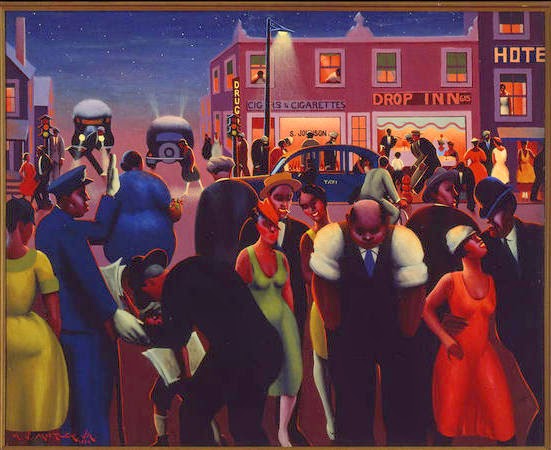

Artist Archibald J. Motley Jr.'s Jazz Age imagery on display at LACMA: Achibald J. Motley Jr. was an artist intrigued by the night. It is there in a large number of his paintings, which tap into the joys and dramas of life after dark, onstage and backstage, in the streets of Chicago or during a feverish nighttime church service. His neon-lighted scenes emerged from the Midwestern wing of the Harlem Renaissance, as the African American community asserted itself nearly a century ago as a major creative force in art, literature and music. "Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist," on exhibition through Feb. 1 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is the first wide-ranging survey of his vivid work since a 1991show at the Chicago History Museum.

With about 45 paintings, the LACMA show (which opened at Duke's Nasher Museum of Art) is not a full retrospective but represents "the highlights of an amazing career," says Powell. While the early portraits, Powell says, "deal with family and friends, 'Tongues (Holy Rollers)' is the extended family: The family of the community. The family of black folks at church, at the park, in clubs. It's all a big reflection on Jazz Age Chicago." The exhibition is organized into sections focused on his early portraits, commentary on race, his year in Paris, and Chicago street and night scenes. The later section includes the sound of vintage jazz recordings pumped into the room. While Motley's initial renown in art circles began to fade in the 1940s as interest grew in abstraction and attention focused even more on New York City, his work was rediscovered during the black arts movement of the '60s and '70s, Powell says. Source: www.latimes.com

Friday, October 31, 2014

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

The Man with X-Ray Eyes: a cautionary tale for Halloween, "Premature Burial" (1962)

Halloween is a special time. It is the one time of year when everyone gives of themselves. What they give can be anything from candy to a scare. We thought this October, we here at Mania would give you 31 Days of Horror films. Get ready for 31 films that will run gauntlet from scary to campy.

From the opening score by Les Baxter to director Roger Corman’s final shock the Man with X-Ray Eyes (formerly known as X) is a time capsule of the Sixties B horror genre worth every penny Corman put on screen. Ray Milland portrays Dr. James Xavier, a man obsessed with discovering the secrets to better and clearer vision. His experiments are not to benefit mankind with better eyesight but to see past all that is hidden from the world and what lies beyond. Xavier believes that his visionary experiment will bring the medical field to a new level where doctors have the capabilities to be living x-ray machines.

It is this obsession that is his downfall and his own shortsightedness that will cause his self-experimentation to go horribly wrong. Really there isn’t anything new here in the realm of mad scientist plots. They go all the way back to Mary Shelly’s Doctor Victor Frankenstein. Man wants answers and will ignore the laws of both man and nature to find them, ending with one horrific conclusion. The Sixties were uncertain times. The United States was rediscovering itself in terms of what was acceptable or not for race, sex and freedom. Corman walks a tightrope by showing his perception of the era and how men and women saw each other instead of focusing on his original intent, a horror film. One example of how he accomplished this is at a swinging dance party after Xavier has the ability to see them without their clothes. Another example deals with how the poor and destitute see Xavier as their savior. He is reduced to performing parlor tricks with his eyes to make ends meet.

The ending is a bigger than expected finale given the budget and the era of the film. Corman doesn’t waste a single penny on screen and gives the audience a ride on a plot that has been done to death. The final moments are a brilliant conclusion and will leave no fan of the genre disappointed. The Man with X-Ray Eyes is a great cautionary tale and the perils of science and man’s quest for knowledge.

Source: www.mania.com

"Premature Burial" (1962) directed by Roger Corman, starring Ray Milland, Hazel Court and Heather Angel, based on a short story by Edgar Allan Poe (published in 1844 in The Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper).

Set in the early dark Victorian-era 1830s or '40s (also similar to Charles Dickens' fiction of rain-soaked London streets), we follow Guy Carrell (Ray Milland), who is obsessed with the fear of death. He is most obsessed with the fear of being buried alive. Though his fiancee Emily (Hazel Court) says he has nothing to be afraid of, he still thinks he will be buried alive (a common fear and in reality an occasional occurrence). So deluded, he seeks help from a few people, including his sister Kate (Heather Angel), but he still is haunted by the fear of death and the sense that someone close wants him dead.

From the opening score by Les Baxter to director Roger Corman’s final shock the Man with X-Ray Eyes (formerly known as X) is a time capsule of the Sixties B horror genre worth every penny Corman put on screen. Ray Milland portrays Dr. James Xavier, a man obsessed with discovering the secrets to better and clearer vision. His experiments are not to benefit mankind with better eyesight but to see past all that is hidden from the world and what lies beyond. Xavier believes that his visionary experiment will bring the medical field to a new level where doctors have the capabilities to be living x-ray machines.

It is this obsession that is his downfall and his own shortsightedness that will cause his self-experimentation to go horribly wrong. Really there isn’t anything new here in the realm of mad scientist plots. They go all the way back to Mary Shelly’s Doctor Victor Frankenstein. Man wants answers and will ignore the laws of both man and nature to find them, ending with one horrific conclusion. The Sixties were uncertain times. The United States was rediscovering itself in terms of what was acceptable or not for race, sex and freedom. Corman walks a tightrope by showing his perception of the era and how men and women saw each other instead of focusing on his original intent, a horror film. One example of how he accomplished this is at a swinging dance party after Xavier has the ability to see them without their clothes. Another example deals with how the poor and destitute see Xavier as their savior. He is reduced to performing parlor tricks with his eyes to make ends meet.

The ending is a bigger than expected finale given the budget and the era of the film. Corman doesn’t waste a single penny on screen and gives the audience a ride on a plot that has been done to death. The final moments are a brilliant conclusion and will leave no fan of the genre disappointed. The Man with X-Ray Eyes is a great cautionary tale and the perils of science and man’s quest for knowledge.

Source: www.mania.com

"Premature Burial" (1962) directed by Roger Corman, starring Ray Milland, Hazel Court and Heather Angel, based on a short story by Edgar Allan Poe (published in 1844 in The Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper).

Set in the early dark Victorian-era 1830s or '40s (also similar to Charles Dickens' fiction of rain-soaked London streets), we follow Guy Carrell (Ray Milland), who is obsessed with the fear of death. He is most obsessed with the fear of being buried alive. Though his fiancee Emily (Hazel Court) says he has nothing to be afraid of, he still thinks he will be buried alive (a common fear and in reality an occasional occurrence). So deluded, he seeks help from a few people, including his sister Kate (Heather Angel), but he still is haunted by the fear of death and the sense that someone close wants him dead.

Friday, October 24, 2014

Marlene Dietrich: exhibit on LACMA, Donald Spoto's biography

"It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily." —Marlene Dietrich in "Shanghai Express" (1932)

LACMA is currently hosting a fabulous new exhibit on Hollywood costume design called Hollywood Costume, running until March 2, 2015, at the Wilshire May Company building. Concurrently the LACMA Tuesday senior matinee has scheduled its monthly films built around a famed designer. October is devoted to Paramount's Travis Banton, who with Adrian (MGM), Orry-Kelly (Warner Brothers) and Edith Head (Paramount) helped create the gorgeous movie costumes of the Golden Age of Hollywood. Banton created the great Marlene Dietrich gowns that she wore through her '30s Paramount career.

Dietrich's first American film, Morocco, screened this week, and it was a revelation—not so much for the Dietrich costumes but for how the actress was first presented to American films audiences in 1930. Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo were icons and eternal symbols of glamour from the very beginning of their careers. Both actresses were foreign born stars (Germany and Sweden) whose status and popularity was more rarefied than home-grown product. Critics and big city audiences appreciated these beauties, but most Americans wanted Jean Harlow and Myrna Loy. Garbo was considered the actress, Dietrich the symbol of foreign mystery and allure.

Josef Von Sternberg had made Marlene Dietrich a star with the classic The Blue Angel. Watching this film today, it is hard to figure out how she became a legend. She was plump and not particularly alluring. Van Sternberg brought her to Hollywood, and together they made six films together that are revered today as classics. Von Sternberg convinced Dietrich to lose weight, and her glamorous image—created by striking camera work and inventive direction—was responsible for the icon known as Marlene Dietrich. Watching Morocco the other day was fascinating in that you could see Dietrich move from amateur to star as the film progresses. In the beginning Dietrich looks plump and unsure of herself in her two musical numbers. Later, as her obsession with legionnaire Gary Cooper increases, you see the transformation from minor actress to assured star. Morocco is a terrible movie but pretty campy, especially at the end when Marlene kicks off her high heals and staggers into the desert with the other female camp followers to stay with her man. Ironically, Dietrich received her only Oscar nomination for this kitschy role.

In just two short years, "Marlene Dietrich, icon extraordinaire" was born in Shanghai Express—probably the best of the Von Sternberg films. The baby fat is gone, the hair is longer and more lustrous, and her face has a sculpted look backed by feathers and luminous photography. As visually striking as the Von Sternberg films were, they threatened to destroy Dietrich the actress. By the end of the '30s she was called box-office poison and in dire need of a career change. She found it playing Frenchie in the great western/comedy Destry Rides Again with James Stewart. Dietrich was still glamorous, but she was alive and funny for the first time on-screen.

During the war years, Marlene Dietrich devoted herself to supporting the U.S. war effort against her homeland. She had famously turned down Adolf Hitler's offer to return to Germany as a superstar. Touring war zones and giving all her support to defeating Germany made her a legend in the United States and a pariah in her native land. Dietrich was given the Medal of Freedom by the U.S. in 1945. Marlene Dietrich became truly interesting as an actress after the the war. She may be the only actress from that era to actually look better as she got older.

In 1948, Dietrich gave her greatest performance in Billy Wilder's A Foreign Affair. At age 46 she looked better than she had in Morocco back in 1930. And her performance was staggering. Yet there was no Oscar nomination, and the film was so controversial that it vanished quickly. Loretta Young won the 1947 Best Actress award for The Farmer's Daughter. Dietrich should have romped home with this award for her spectacular performance. In 1950 she stole Alfred Hitchcock's Stagefright from a pallid Jane Wyman, and in 1957 gave another magnificent performance as Christine Vole in Billy Wilder's courtroom thriller Witness for the Prosecution. Playing the German wife of accused murderer Tyrone Power, Dietrich was amazing, still the glamour icon deep into her 50s.

One last great role came with her hysterical cameo in Orson Welles' Touch of Evil. Looking like she was doing retakes from her 1947 camp classic Golden Earrings, Dietrich had a field day as the all-knowing Tanya. Dietrich continued her career as a singer and sex symbol for the next 20 years. After a disastrous stage fall, she retreated to her Paris apartment and was a total recluse for the last 11 years of her life. Academy Award-winner Max Shell made a documentary about the fabulous star. Released in 1984, Marlene was extravagantly reviewed even though only Dietrich's voice was used as she refused to be photographed. As Norma Desmond exclaimed in Sunset Boulevard, "Great stars are ageless," but great stars like Dietrich were smart enough to retreat behind the legend. Marlene Dietrich is a gay icon not only because of her fabulous film career—her bisexual lifestyle is filled with enough famous lovers of both sexes to stagger the imagination.

Marlene Dietrich was the eternal symbol of beauty and glamor for almost 50 years. But if you have to pick just one Dietrich film to watch, get Billy Wilder's A Foreign Affair. It is all there—the voice, the face, great songs, gorgeous cinematography, brilliant Wilder dialog and the greatest performance the legend known as Marlene Dietrich ever gave. Source: www.frontiersla.com

Dietrich smoothly engineered an evening à deux at Horn Avenue, and soon there flourished an affair that was (at least for Cooper) as hot as Morocco itself. This was no real challenge for Dietrich, since Cooper, although married, readily succumbed to the offer; he had also been involved with Clara Bow and, even more seriously, with Lupe Velez. Of course, von Sternberg was not at all pleased with this new development, but he knew better than to complain. Some people can evoke from their lovers an attention that is frankly deferential. This ability Dietrich seems to have raised to the level of a fine art, for remarkably often in her life her lovers were not only grateful admirers but somehow felt bound to her.

Men were especially vulnerable to this, Cooper among them: for the remainder of Morocco, he was her devoted ally, far more ardent to please and attend her in life than in the story they were filming. Von Sternberg, though firmly out of this romantic running of the bulls, quietly raged with jealousy and resentment, according to both Dietrich (“They didn’t like each other . . . [it was] jealousy”) and actor Joel McCrea, a friend of Cooper’s (“Jo was jealous . . . and Cooper hated him”). But to make things more complicated still, Cooper soon had his own reasons for jealousy when he learned that Maurice Chevalier had briefly become a rival. Chevalier’s autobiography claims the friendship was “simply camaraderie,” but his wife used it as the basis for a successful divorce petition. It would be easy to regard Marlene Dietrich’s vigorous sexual life as irresponsible, frankly hedonistic or even symptomatic of an almost obsessive carnality. But her affairs, no matter how brief or nonexclusive, were always focussed and intense, never merely casual, anonymous trysts. Lavish in bestowing amatory favors, Dietrich in fact equated sex more with the offering of comfort —or perhaps more accurately, the complex, benevolent control she exerted in romances was her gratification. Sex was something nurturing she offered those she respected (like von Sternberg), those she thought were lonely (like Chevalier) or those she thought to be in need (like Cooper, who complained, poor man, that he was being nagged by both his wife and by Lupe Velez).

Essentially a woman of clear preferences and antipathies, Dietrich concealed none of them. She disliked most modern art (von Sternberg’s occasional tutorials notwithstanding), noodles, horse races, evangelism, fish, after-dinner speeches, politics, American sandwiches, opera and slang; she favored Punch and Judy shows, apple strudel, circus performers, speeding in an open roadster, pickles, perfumes, romantic novels by Sudermann and doleful poetry by Heine. There was, however, nothing about her of the Byronic heroine, and her attitude toward intimacy was a great deal simpler than von Sternberg’s, and without much reflection. “I had nothing to do with my birth,” she said around this time, “and I most likely will have nothing to do with my future. My philosophy of life is simply one of resignation.”

Her convictions, accordingly, were based simply on experience, and this had unequivocally taught her that Josef von Sternberg was certainly good for her. While he saw her as a beautiful woman who could wreak emotional havoc by simply being, he was at the same time one of the moths drawn ineluctably to her flame. Dietrich was an exciting woman whose eroticism was, to those she liked, neither cheaply accessible nor teasingly withheld. For von Sternberg, she also seemed to promise more than she at any one time delivered—not only more sensual satisfaction but also more artistic possibilities for her exploitation as an actress. However, intimacy revealed to von Sternberg another part of her nature: that there was perhaps nothing in her emotional life reserved for only one or even a dozen people she liked. And this realization prompted von Sternberg to withdraw.

The coolly detached seducer of the self-destructive man, she was an earthy woman who simply cavorted according to her nature (thus The Blue Angel). But the tarnished performer could also be a faithful follower (Morocco), a hooker with a curious higher morality (Dishonored), a weary traveler living by wit and charm (Shanghai Express), a mother devoted to her child (Blonde Venus). Although she always insisted her roles had nothing to do with her true character, the truth was just the opposite: they were in fact coded chapters in a kind of tribute-biography von Sternberg made of her, a series of essays that could have been called “All the Things You Are.” But he also saw her, in everyday life, as capricious, even sometimes shallow; his fantasy about her was therefore being chastened and his goddess revealed as thoroughly human, frail and fallible.

Dietrich was becoming more and more blunt in pursuing actresses she found attractive; among them were Paramount’s Carole Lombard and Frances Dee, whose unregenerate heterosexuality did not dissuade Dietrich from her usual stratagems of flower deliveries and romantic blandishments. Lombard, a beautiful, brash blonde, was unamused: “If you want something,” she told Dietrich after finding one too many sweet notes and posies in her dressing room at Paramount, “you come on down when I’m there. I’m not going to chase you.”

Dietrich took Hemingway as something of a counselor and father-figure, calling him (as did others) her “Papa.” She was most of all one of his buddies, and in this regard the relationship was perhaps unique in his life. By a kind of tacit common consent, they were never lovers—a situation that might have aborted friendship with this man who simultaneously revered and feared women. His “loveliest dreams,” as he said, were often of Dietrich, who was “awfully nice in dreams”—a sentiment worthy of von Sternberg. With Dietrich, Hemingway could simultaneously enjoy the nurturing adulation of a beautiful and famous woman and the matey fellowship of someone who never threatened him by demanding sex; in this way, Marlene Dietrich was the ideal Hemingway heroine. He called her 'The Kraut'.

Dietrich’s cavalier independence and the role of lover primus inter pares was finally too much for Jean Gabin; he married the French actress Maria Mauban. This was a devastating blow to Dietrich, who could never understand why a man she still loved (or ever had loved) would commit to another woman. When Robert Kennedy asked her, at a Washington luncheon in 1963, why she said she left Jean Gabin, she replied, “Because he wanted to marry me. I hate marriage. It is an immoral institution. But he still loves me.” The Gabin affair ended in 1946. Dietrich now had no prospects of European film work and therefore accepted an offer from Hollywood to appear in a film called Golden Earrings. Because she had been absent from Hollywood three full years (and had not starred in a successful film since 1939), Leisen had to convince Paramount that Dietrich was the right choice to play Lydia, a vulgar but seductive Middle European gypsy who helps a British intelligence officer smuggle a poison gas formula out of Nazi Germany just before the war by disguising him as her peasant husband. When she was first offered the role, Dietrich was still in Europe and visited gypsy camps to see how the women looked, dressed and behaved.

Now at the studio for wardrobe and makeup tests, she assured Leisen she would play Lydia with complete fidelity to realism—to European neorealism, in fact, which flinched at nothing. This she did stonishingly well, for although Dietrich could not of course completely abandon her pretension to youthful beauty (nor would the studio have desired it), she dispatched the role of a greasy, sloppy gypsy with the kind of fresh comic panache not seen since her Frenchy in Destry Rides Again.

As a sex-starved wench, she swoops down on the stuffy hero played by Ray Milland, supervising his transformation into a Hungarian peasant. Munching bread, gnawing on a fish-head supper, spitting for good luck, diving for Milland’s lips and chest, she is the complete, manhungry virago—at once crude, funny and sensuous throughout the aridly incredible narrative. “You look like a wild bull!” she whispers to Milland after she has finished with his disguising makeup, pierced his ears and clipped on the golden earrings; then she nearly growls, “The girls—will—go—mad—for you!” Often resembling the seductive young Gloria Swanson, Dietrich does not simply breathe in this picture; she seems to exhale fire.

But the appealing comic nonsense of the completed Golden Earrings did not apply to the rigors of production, for there were bitter feuds. Milland, who had just won an Oscar playing an alcoholic in Billy Wilder’s harrowing film The Lost Weekend, disliked Dietrich and feared she would steal the picture (which she handily did). He also found her commitment to realism somewhat revolting—especially in the eating scene, when she repeatedly stuck a fish in her mouth, sucked out the eye, pulled off the head, swallowed it and (after Leisen had shot the scene) promptly stuck her finger in her throat and vomited. The Legion of Decency’s censure (she could not keep her hands off Milland) was officially an acute embarrassment for the studio, although it was also splendid free publicity: the picture returned three million dollars in the next two years.

From Paris that summer of 1947, Dietrich wrote to her Paramount hairdresser, Nellie Manley, that she was “living quietly at the Hotel Georges V, cooking whatever can be cooked. The attitude and the feelings of the people are not as good as they were during the war. It is depressing, but not hopeless.” Her fortunes improved that August, when Billy Wilder stopped in Paris to visit her after filming exterior shots for a forthcoming “black comedy” about life in occupied postwar Berlin; he offered Dietrich the role of Erika von Schlütow in the picture, to be called A Foreign Affair. At first she rejected it, hesitating to play the German mistress of an American army officer who loses him to a winsome visiting congresswoman and is then taken away by military police after her Nazi past is revealed.

With his patented brand of acerbic moral cynicism, Wilder had prepared A Foreign Affair as a satiric criticism of widespread military corruption amid the ruins of Berlin, of the Allied involvement in a shameful black market, and of the self-righteous abuse of German civilians by occupying American soldiers. When filming began in December, Dietrich’s co-star as the prissy, investigating congresswoman was Jean Arthur; the leading man was John Lund; and the pianist in the cabaret was none other than Hollander himself, invited in tribute to his long association as Dietrich’s composer.

Like Pasternak, Wilder understood the value of deglamorizing Dietrich. Her first appearance in A Foreign Affair goes beyond anything in Golden Earrings: her hair is unbrushed, her face smirched with toothpaste, water trickles from her mouth as she brushes and gargles. This character is no Amy Jolly, no Concha Perez. As the story proceeds, it becomes clear that Erika can manipulate American officers as easily as she did Nazis, one of whom was her attended as a fashionable companion. But she has suffered privately, socially and by postwar deprivation for her guilty past; her act at the Lorelei cabaret, singing “Black Market” and “The Ruins of Berlin,” expresses her cool cynicism, her distrust of any nation’s claim to moral supremacy and her necessary, fearful suspicion of everyone.

The role was perfect for Dietrich, for she had been long confirmed by Hollywood as von Sternberg’s icon of the tarnished woman masked with pain and capable of love and all of whom she easily the sudden acknowledgment of her own need for tenderness and forgiveness— indeed, for redemption from the past. “I knew,” Wilder said years later, “that whatever obsession she had with her appearance, she was also a thorough professional. From the time she met von Sternberg she had always been very interested in his magic tricks with the camera—tricks she tried to teach every cameraman in later pictures.” -"Blue Angel: the Life of Marlene Dietrich" (2000) by Donald Spoto

LACMA is currently hosting a fabulous new exhibit on Hollywood costume design called Hollywood Costume, running until March 2, 2015, at the Wilshire May Company building. Concurrently the LACMA Tuesday senior matinee has scheduled its monthly films built around a famed designer. October is devoted to Paramount's Travis Banton, who with Adrian (MGM), Orry-Kelly (Warner Brothers) and Edith Head (Paramount) helped create the gorgeous movie costumes of the Golden Age of Hollywood. Banton created the great Marlene Dietrich gowns that she wore through her '30s Paramount career.

Dietrich's first American film, Morocco, screened this week, and it was a revelation—not so much for the Dietrich costumes but for how the actress was first presented to American films audiences in 1930. Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo were icons and eternal symbols of glamour from the very beginning of their careers. Both actresses were foreign born stars (Germany and Sweden) whose status and popularity was more rarefied than home-grown product. Critics and big city audiences appreciated these beauties, but most Americans wanted Jean Harlow and Myrna Loy. Garbo was considered the actress, Dietrich the symbol of foreign mystery and allure.

Josef Von Sternberg had made Marlene Dietrich a star with the classic The Blue Angel. Watching this film today, it is hard to figure out how she became a legend. She was plump and not particularly alluring. Van Sternberg brought her to Hollywood, and together they made six films together that are revered today as classics. Von Sternberg convinced Dietrich to lose weight, and her glamorous image—created by striking camera work and inventive direction—was responsible for the icon known as Marlene Dietrich. Watching Morocco the other day was fascinating in that you could see Dietrich move from amateur to star as the film progresses. In the beginning Dietrich looks plump and unsure of herself in her two musical numbers. Later, as her obsession with legionnaire Gary Cooper increases, you see the transformation from minor actress to assured star. Morocco is a terrible movie but pretty campy, especially at the end when Marlene kicks off her high heals and staggers into the desert with the other female camp followers to stay with her man. Ironically, Dietrich received her only Oscar nomination for this kitschy role.

In just two short years, "Marlene Dietrich, icon extraordinaire" was born in Shanghai Express—probably the best of the Von Sternberg films. The baby fat is gone, the hair is longer and more lustrous, and her face has a sculpted look backed by feathers and luminous photography. As visually striking as the Von Sternberg films were, they threatened to destroy Dietrich the actress. By the end of the '30s she was called box-office poison and in dire need of a career change. She found it playing Frenchie in the great western/comedy Destry Rides Again with James Stewart. Dietrich was still glamorous, but she was alive and funny for the first time on-screen.

During the war years, Marlene Dietrich devoted herself to supporting the U.S. war effort against her homeland. She had famously turned down Adolf Hitler's offer to return to Germany as a superstar. Touring war zones and giving all her support to defeating Germany made her a legend in the United States and a pariah in her native land. Dietrich was given the Medal of Freedom by the U.S. in 1945. Marlene Dietrich became truly interesting as an actress after the the war. She may be the only actress from that era to actually look better as she got older.

In 1948, Dietrich gave her greatest performance in Billy Wilder's A Foreign Affair. At age 46 she looked better than she had in Morocco back in 1930. And her performance was staggering. Yet there was no Oscar nomination, and the film was so controversial that it vanished quickly. Loretta Young won the 1947 Best Actress award for The Farmer's Daughter. Dietrich should have romped home with this award for her spectacular performance. In 1950 she stole Alfred Hitchcock's Stagefright from a pallid Jane Wyman, and in 1957 gave another magnificent performance as Christine Vole in Billy Wilder's courtroom thriller Witness for the Prosecution. Playing the German wife of accused murderer Tyrone Power, Dietrich was amazing, still the glamour icon deep into her 50s.

One last great role came with her hysterical cameo in Orson Welles' Touch of Evil. Looking like she was doing retakes from her 1947 camp classic Golden Earrings, Dietrich had a field day as the all-knowing Tanya. Dietrich continued her career as a singer and sex symbol for the next 20 years. After a disastrous stage fall, she retreated to her Paris apartment and was a total recluse for the last 11 years of her life. Academy Award-winner Max Shell made a documentary about the fabulous star. Released in 1984, Marlene was extravagantly reviewed even though only Dietrich's voice was used as she refused to be photographed. As Norma Desmond exclaimed in Sunset Boulevard, "Great stars are ageless," but great stars like Dietrich were smart enough to retreat behind the legend. Marlene Dietrich is a gay icon not only because of her fabulous film career—her bisexual lifestyle is filled with enough famous lovers of both sexes to stagger the imagination.

Marlene Dietrich was the eternal symbol of beauty and glamor for almost 50 years. But if you have to pick just one Dietrich film to watch, get Billy Wilder's A Foreign Affair. It is all there—the voice, the face, great songs, gorgeous cinematography, brilliant Wilder dialog and the greatest performance the legend known as Marlene Dietrich ever gave. Source: www.frontiersla.com

Dietrich smoothly engineered an evening à deux at Horn Avenue, and soon there flourished an affair that was (at least for Cooper) as hot as Morocco itself. This was no real challenge for Dietrich, since Cooper, although married, readily succumbed to the offer; he had also been involved with Clara Bow and, even more seriously, with Lupe Velez. Of course, von Sternberg was not at all pleased with this new development, but he knew better than to complain. Some people can evoke from their lovers an attention that is frankly deferential. This ability Dietrich seems to have raised to the level of a fine art, for remarkably often in her life her lovers were not only grateful admirers but somehow felt bound to her.

Men were especially vulnerable to this, Cooper among them: for the remainder of Morocco, he was her devoted ally, far more ardent to please and attend her in life than in the story they were filming. Von Sternberg, though firmly out of this romantic running of the bulls, quietly raged with jealousy and resentment, according to both Dietrich (“They didn’t like each other . . . [it was] jealousy”) and actor Joel McCrea, a friend of Cooper’s (“Jo was jealous . . . and Cooper hated him”). But to make things more complicated still, Cooper soon had his own reasons for jealousy when he learned that Maurice Chevalier had briefly become a rival. Chevalier’s autobiography claims the friendship was “simply camaraderie,” but his wife used it as the basis for a successful divorce petition. It would be easy to regard Marlene Dietrich’s vigorous sexual life as irresponsible, frankly hedonistic or even symptomatic of an almost obsessive carnality. But her affairs, no matter how brief or nonexclusive, were always focussed and intense, never merely casual, anonymous trysts. Lavish in bestowing amatory favors, Dietrich in fact equated sex more with the offering of comfort —or perhaps more accurately, the complex, benevolent control she exerted in romances was her gratification. Sex was something nurturing she offered those she respected (like von Sternberg), those she thought were lonely (like Chevalier) or those she thought to be in need (like Cooper, who complained, poor man, that he was being nagged by both his wife and by Lupe Velez).

Essentially a woman of clear preferences and antipathies, Dietrich concealed none of them. She disliked most modern art (von Sternberg’s occasional tutorials notwithstanding), noodles, horse races, evangelism, fish, after-dinner speeches, politics, American sandwiches, opera and slang; she favored Punch and Judy shows, apple strudel, circus performers, speeding in an open roadster, pickles, perfumes, romantic novels by Sudermann and doleful poetry by Heine. There was, however, nothing about her of the Byronic heroine, and her attitude toward intimacy was a great deal simpler than von Sternberg’s, and without much reflection. “I had nothing to do with my birth,” she said around this time, “and I most likely will have nothing to do with my future. My philosophy of life is simply one of resignation.”

Her convictions, accordingly, were based simply on experience, and this had unequivocally taught her that Josef von Sternberg was certainly good for her. While he saw her as a beautiful woman who could wreak emotional havoc by simply being, he was at the same time one of the moths drawn ineluctably to her flame. Dietrich was an exciting woman whose eroticism was, to those she liked, neither cheaply accessible nor teasingly withheld. For von Sternberg, she also seemed to promise more than she at any one time delivered—not only more sensual satisfaction but also more artistic possibilities for her exploitation as an actress. However, intimacy revealed to von Sternberg another part of her nature: that there was perhaps nothing in her emotional life reserved for only one or even a dozen people she liked. And this realization prompted von Sternberg to withdraw.

The coolly detached seducer of the self-destructive man, she was an earthy woman who simply cavorted according to her nature (thus The Blue Angel). But the tarnished performer could also be a faithful follower (Morocco), a hooker with a curious higher morality (Dishonored), a weary traveler living by wit and charm (Shanghai Express), a mother devoted to her child (Blonde Venus). Although she always insisted her roles had nothing to do with her true character, the truth was just the opposite: they were in fact coded chapters in a kind of tribute-biography von Sternberg made of her, a series of essays that could have been called “All the Things You Are.” But he also saw her, in everyday life, as capricious, even sometimes shallow; his fantasy about her was therefore being chastened and his goddess revealed as thoroughly human, frail and fallible.

Dietrich was becoming more and more blunt in pursuing actresses she found attractive; among them were Paramount’s Carole Lombard and Frances Dee, whose unregenerate heterosexuality did not dissuade Dietrich from her usual stratagems of flower deliveries and romantic blandishments. Lombard, a beautiful, brash blonde, was unamused: “If you want something,” she told Dietrich after finding one too many sweet notes and posies in her dressing room at Paramount, “you come on down when I’m there. I’m not going to chase you.”

Dietrich took Hemingway as something of a counselor and father-figure, calling him (as did others) her “Papa.” She was most of all one of his buddies, and in this regard the relationship was perhaps unique in his life. By a kind of tacit common consent, they were never lovers—a situation that might have aborted friendship with this man who simultaneously revered and feared women. His “loveliest dreams,” as he said, were often of Dietrich, who was “awfully nice in dreams”—a sentiment worthy of von Sternberg. With Dietrich, Hemingway could simultaneously enjoy the nurturing adulation of a beautiful and famous woman and the matey fellowship of someone who never threatened him by demanding sex; in this way, Marlene Dietrich was the ideal Hemingway heroine. He called her 'The Kraut'.

Dietrich’s cavalier independence and the role of lover primus inter pares was finally too much for Jean Gabin; he married the French actress Maria Mauban. This was a devastating blow to Dietrich, who could never understand why a man she still loved (or ever had loved) would commit to another woman. When Robert Kennedy asked her, at a Washington luncheon in 1963, why she said she left Jean Gabin, she replied, “Because he wanted to marry me. I hate marriage. It is an immoral institution. But he still loves me.” The Gabin affair ended in 1946. Dietrich now had no prospects of European film work and therefore accepted an offer from Hollywood to appear in a film called Golden Earrings. Because she had been absent from Hollywood three full years (and had not starred in a successful film since 1939), Leisen had to convince Paramount that Dietrich was the right choice to play Lydia, a vulgar but seductive Middle European gypsy who helps a British intelligence officer smuggle a poison gas formula out of Nazi Germany just before the war by disguising him as her peasant husband. When she was first offered the role, Dietrich was still in Europe and visited gypsy camps to see how the women looked, dressed and behaved.

Now at the studio for wardrobe and makeup tests, she assured Leisen she would play Lydia with complete fidelity to realism—to European neorealism, in fact, which flinched at nothing. This she did stonishingly well, for although Dietrich could not of course completely abandon her pretension to youthful beauty (nor would the studio have desired it), she dispatched the role of a greasy, sloppy gypsy with the kind of fresh comic panache not seen since her Frenchy in Destry Rides Again.

As a sex-starved wench, she swoops down on the stuffy hero played by Ray Milland, supervising his transformation into a Hungarian peasant. Munching bread, gnawing on a fish-head supper, spitting for good luck, diving for Milland’s lips and chest, she is the complete, manhungry virago—at once crude, funny and sensuous throughout the aridly incredible narrative. “You look like a wild bull!” she whispers to Milland after she has finished with his disguising makeup, pierced his ears and clipped on the golden earrings; then she nearly growls, “The girls—will—go—mad—for you!” Often resembling the seductive young Gloria Swanson, Dietrich does not simply breathe in this picture; she seems to exhale fire.

But the appealing comic nonsense of the completed Golden Earrings did not apply to the rigors of production, for there were bitter feuds. Milland, who had just won an Oscar playing an alcoholic in Billy Wilder’s harrowing film The Lost Weekend, disliked Dietrich and feared she would steal the picture (which she handily did). He also found her commitment to realism somewhat revolting—especially in the eating scene, when she repeatedly stuck a fish in her mouth, sucked out the eye, pulled off the head, swallowed it and (after Leisen had shot the scene) promptly stuck her finger in her throat and vomited. The Legion of Decency’s censure (she could not keep her hands off Milland) was officially an acute embarrassment for the studio, although it was also splendid free publicity: the picture returned three million dollars in the next two years.

From Paris that summer of 1947, Dietrich wrote to her Paramount hairdresser, Nellie Manley, that she was “living quietly at the Hotel Georges V, cooking whatever can be cooked. The attitude and the feelings of the people are not as good as they were during the war. It is depressing, but not hopeless.” Her fortunes improved that August, when Billy Wilder stopped in Paris to visit her after filming exterior shots for a forthcoming “black comedy” about life in occupied postwar Berlin; he offered Dietrich the role of Erika von Schlütow in the picture, to be called A Foreign Affair. At first she rejected it, hesitating to play the German mistress of an American army officer who loses him to a winsome visiting congresswoman and is then taken away by military police after her Nazi past is revealed.

With his patented brand of acerbic moral cynicism, Wilder had prepared A Foreign Affair as a satiric criticism of widespread military corruption amid the ruins of Berlin, of the Allied involvement in a shameful black market, and of the self-righteous abuse of German civilians by occupying American soldiers. When filming began in December, Dietrich’s co-star as the prissy, investigating congresswoman was Jean Arthur; the leading man was John Lund; and the pianist in the cabaret was none other than Hollander himself, invited in tribute to his long association as Dietrich’s composer.

Like Pasternak, Wilder understood the value of deglamorizing Dietrich. Her first appearance in A Foreign Affair goes beyond anything in Golden Earrings: her hair is unbrushed, her face smirched with toothpaste, water trickles from her mouth as she brushes and gargles. This character is no Amy Jolly, no Concha Perez. As the story proceeds, it becomes clear that Erika can manipulate American officers as easily as she did Nazis, one of whom was her attended as a fashionable companion. But she has suffered privately, socially and by postwar deprivation for her guilty past; her act at the Lorelei cabaret, singing “Black Market” and “The Ruins of Berlin,” expresses her cool cynicism, her distrust of any nation’s claim to moral supremacy and her necessary, fearful suspicion of everyone.

The role was perfect for Dietrich, for she had been long confirmed by Hollywood as von Sternberg’s icon of the tarnished woman masked with pain and capable of love and all of whom she easily the sudden acknowledgment of her own need for tenderness and forgiveness— indeed, for redemption from the past. “I knew,” Wilder said years later, “that whatever obsession she had with her appearance, she was also a thorough professional. From the time she met von Sternberg she had always been very interested in his magic tricks with the camera—tricks she tried to teach every cameraman in later pictures.” -"Blue Angel: the Life of Marlene Dietrich" (2000) by Donald Spoto

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

"The Trouble with Women" (1947) & "The Imperfect Lady" - Ray Milland and Teresa Wright

The newspapers of a Midwest college town announce the arrival of psychology professor Gilbert Sedley (Ray Milland) to the school. Gilbert has just published a book based on his experiments in hypnosis that supposedly prove that women have an unconscious desire to be subjugated. Joe McBride (Brian Donlevy), city editor of the Globe , sends reporter Kate Farrell (Teresa Wright), with whom he is in love, to interview Gilbert. Kate writes an article under the pseudonym "Martha Motherly" and accuses Gilbert of advocating wife-beating. Gilbert sues the Globe for slander, and unaware that Kate is "Martha Motherly," begins to fall in love with her.

Kate enrolls in Gilbert's class and antagonizes him, hoping he will hit her in front of Globe photographer Herman Lupin. Gilbert, meanwhile, takes meticulous notes on his "animalistic" chemical reactions to Kate's womanhood. Gilbert finally gives in to his urges to kiss Kate, but Agnes spoils their romance by telling him that Kate is "Martha Motherly." Kate quits the newspaper and prepares to return to her home town of St. Paul, Minnesota. Upon learning that Gilbert plans to resign from the university, Kate appeals to the board of regents and confesses her part in the scandal. Joe also quits the newspaper so that Kate will marry him, but she refuses. After a colleague tells Gilbert that Kate came to his defense, he has her subpoenaed for his libel suit trial to keep her from leaving town. In court, Gilbert uses hypnosis to get Kate to agree to marry him but she revives and admits that it was not she but the judge whom he hypnotized. Seeing that Kate and Gilbert are in love, Joe returns to the Globe and writes a story about how a Svengali courted his girl in court. Source: www.tcm.com

Quotes by Teresa Wright as Kate Farrell in THE TROUBLE WITH WOMEN (1947):

-"Being a maid, sir, is womanly work. I like being subjugated."

-"I use Tippy's Toothpaste for that radiant smile, and Larson's Lotion is terribly kind to my hands."

-"I didn't get dressed up to meet a bank robber."

The Imperfect Lady is a 1947 American drama film directed by Lewis Allen and starring Ray Milland, Teresa Wright and Cedric Hardwicke, filmed in 1945 and not released until 1947. In the late Victorian Britain an aristocratic politician falls in love with a showgirl. The film is also known by the alternative title Mrs. Loring's Secret.

"Men and women are different, but if women are good enough to run homes and raise children, then their influence ought to be good for politics." -Teresa Wright as Millicent Hopkins in "The Imperfect Lady" (1947).

Kate enrolls in Gilbert's class and antagonizes him, hoping he will hit her in front of Globe photographer Herman Lupin. Gilbert, meanwhile, takes meticulous notes on his "animalistic" chemical reactions to Kate's womanhood. Gilbert finally gives in to his urges to kiss Kate, but Agnes spoils their romance by telling him that Kate is "Martha Motherly." Kate quits the newspaper and prepares to return to her home town of St. Paul, Minnesota. Upon learning that Gilbert plans to resign from the university, Kate appeals to the board of regents and confesses her part in the scandal. Joe also quits the newspaper so that Kate will marry him, but she refuses. After a colleague tells Gilbert that Kate came to his defense, he has her subpoenaed for his libel suit trial to keep her from leaving town. In court, Gilbert uses hypnosis to get Kate to agree to marry him but she revives and admits that it was not she but the judge whom he hypnotized. Seeing that Kate and Gilbert are in love, Joe returns to the Globe and writes a story about how a Svengali courted his girl in court. Source: www.tcm.com

Quotes by Teresa Wright as Kate Farrell in THE TROUBLE WITH WOMEN (1947):

-"Being a maid, sir, is womanly work. I like being subjugated."

-"I use Tippy's Toothpaste for that radiant smile, and Larson's Lotion is terribly kind to my hands."

-"I didn't get dressed up to meet a bank robber."

The Imperfect Lady is a 1947 American drama film directed by Lewis Allen and starring Ray Milland, Teresa Wright and Cedric Hardwicke, filmed in 1945 and not released until 1947. In the late Victorian Britain an aristocratic politician falls in love with a showgirl. The film is also known by the alternative title Mrs. Loring's Secret.

"Men and women are different, but if women are good enough to run homes and raise children, then their influence ought to be good for politics." -Teresa Wright as Millicent Hopkins in "The Imperfect Lady" (1947).

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

"Wide-Eyed in Babylon" by Ray Milland

“I got a job as a junior clerk in the offices of a steel mill, living in the meantime with my father's youngest brother, Frank, who had a son my own age. We went dancing at small local dance halls and chased girls. We drank beer and chased girls. We took up boxing, seriously, at a gym run by the brother of Jimmy Driscoll, The Nonpareil. And then it began to pall. The dreary monotony of our activities, the viciousness of the little gossipings, the small horizons all came to a head the beginning of that June. Our local dentist, a pillar of the Church, furtively dropped his hand onto my crotch while he was examining a wisdom tooth that had been bothering me. In shock and horror, I lashed out and kicked him in the stomach and ran out of there. In my ignorance I was terrified; it was the canal all over again, something beneath the surface, something obscene and horrible. It was my first brush with a homosexual. I am what you might call fervidly heterosexual. It was through Janet MacLeod, that I met most of the friends I have today. And it was through her that I met my wife Mal.

I made a deal with Janet that if she would teach me to play tennis, I would teach her to ride. This led to our going dancing a lot, at George Olson's, Frank Sebastian's Cotton Club, the Coconut Grove, and lots of private homes, as well as to my first and only speakeasy in California, where I became violently ill. It was a dreadful little shack, a bungalow somewhere south of Santa Monica Boulevard. There were about eight or ten people scattered around the living-dining room area, all very quiet and surreptitious. I had the feeling that I must have wandered into an opium den. I went back to Page's club about half a dozen times. I also went to a couple of theatrical parties with Margot St. Leger, and at one of them I met a film actress named Estelle Brody, a very quiet American, who was a star in British films.

It was Estelle who planted the first seed, who started a restlessness in me and the beginnings of discontent. It was she, in her quiet, penetrating way, who first asked if I wanted to stay in the army the rest of my life. I looked at her in some surprise. Suddenly I was aware that I had never thought of the future, that I had never even given much thought beyond tomorrow. Life was too joyful. "Think about it, sonny, and when you have, give me a ring." I had never been very interested in the theater. Up until that time I don't suppose I had seen more than four plays. I think the first one I ever saw was The Only Way, with Martin Harvey and his wife; And the last one was on my nineteenth birthday, at the old Bedford in Camden Town. It was The Silver King, with Tod Slaughter and company. Outside of those few occasions, my theatrical time and money were spent on anything with music.

And, of course, the Palladium, to my mind the greatest variety theater in the world. I went twice a month without fail. I loved it, the individual brilliance of the performers, the marvelous American humor, because fully half the bill came from the United States. I'd ache from laughing at Burns and Allen, Milt Britton's wild and woolly orchestra. Then there was Will Fyffe from Glasgow, Billy Bennett and Albert Rebla from London's East End. And the insane Harry Tate and his golf sketch. But the legitimate theater? I never gave it a thought. The first person I called when I got out the Army was Estelle Brody, but she was on location in Ireland and would not be back for two weeks, so I killed a week going to a couple of plays and popping into Page's for a drink now and again. I met one riotous gal there by the name of Norah Howard. She was going with one of the three Yacht Club Boys, Stewart Ross; the other two were Joe Sargent and Al Barney. They were American and the biggest nightclub hit in London. They remained my friends for many years. I remember Stewart's saying to me, "You in this racket, kid? I mean acting or something? What do you do?" I said I didn't do anything, that I had just come out of the army and was sort of looking around. He said, "Well, get in it, boy. You've got the build for it. Look at me. I can't sing and I don't read music, and here I am playing the piano and singing and making a small fortune, and my two partners are in the same boat. Don't be bashful. They'll never know the difference." I didn't believe him, but I went home thinking that night.

I called Estelle Brody the following Sunday, and she was back. She suggested that I come down to the studio in Elstree on Tuesday and have lunch with her. Then she would have someone take me around and try to explain the goings-on. Just tell the man at the gate, and he would direct me to where she was. I got there at midday, a half hour early, was given the directions, and immediately got lost. I found myself in a cavernous place that looked like an airplane hangar, lit up by what seemed to be at least a thousand searchlights. It was absolutely blinding. After a few moments I saw that it was a huge nightclub with about a hundred and fifty people sitting around, all in evening dress, and all very beautiful. At the foot of a staircase were standing two people, apparently rehearsing a scene. I left and eventually found Estelle, and we went to lunch in the commissary. There were four other people at the table, one of whom turned out to be her director, Norman Walker, and another the studio casting director, whose name was Allen.

Estelle explained to them that this was my first time in a film studio and wouldn't it be a good idea for Allen to give me a couple of days' crowd work so I could see for myself that they weren't all nutty. Allen turned and said, "If you have a dinner jacket I can give you a call for tomorrow morning and you can work on the set you saw today. What do you think?" Suddenly I heard myself saying that I would like it very much but that I knew nothing about makeup and that everybody seemed to be painted orange. "Don't you worry about that. I'll tell one of the extras to make you up. Just report on the set at eight a.m. in your dinner jacket. I'll take care of the call." It was as simple as that. I got the impression that acting was a most insecure calling, peopled mostly by exhibitionists, but seasoned here and there with those who were touched with genius. The ones who kept the theaters open. The upshot of our talk was that I should get an agent. I went to Dan Fish's office. There was a reception room divided by a wooden rail behind which sat a secretary with cropped fair hair and an efficient manner. The rest of the room was taken up with a sofa and a lot of chairs which were filled with what appeared to be the members of a circus. I felt like a leper.

Dan Fish was the agent Ronald Colman had gone to when he was trying to break into pictures. Ronnie had taken his pictures in. Across one of them Dan Fish had written "Nice voice. Short. Splayfooted. Can't act." I've seen it. I finally ended up with Frank Zeitlin, who condescended to take me on as a client. Allen was waiting for me on Stage Two, which had been transformed into what looked like a huge conference room, about sixty feet long and thirty wide. Five or six men were standing at one end. Allen began to explain the reason for the rather hurried call.

They had just started shooting a picture called The Informer. The director was a German named Dr. Arthur Robison, and a stickler for realism. It was a Belgian Browning .22 caliber automatic, a beautiful thing, and held twelve L.R. cartridges. Robison went to the end of the room and drew a chalk circle around an English half-crown, a little larger than a half-dollar. "Fire at that," he said, "as rapidly as possible." "Where from?" I asked. "The other end of the room." I asked permission to take one practice shot, explaining that all firearms behaved differently and that I had never handled this weapon before. I paced the length of the room which, as I thought, was sixty feet. It didn't mean anything but I thought it might impress them. I took careful aim and squeezed off the first shot, and then went down to see where the bullet went. The direction was perfect but the shot was about an inch high, so I went back, made a mental correction and let fly with the other eleven. When the smoke cleared we all went down to see what had happened. Now I have an affidavit, signed by every single one of them, to prove this. All eleven shots had made a hole you could have covered with a quarter. It had taken no more than ten seconds. I couldn't have done it again. Nobody could. I got the job. The pay was to be twenty pounds a week for eight weeks, starting the next day.

I had replaced one of England's most promising film stars, Cyril McLaglen, the brother of wonderful Victor, who, incidentally, had also been a member of the Household Cavalry in the First World War. There were five brothers and believe it or not, their father was a bishop. Their lives were living proof that heredity is a myth, with the possible exception of Andrew, Victor's son, a gentle giant of much intelligence but a lousy golfer. On my idle days I would walk around the stages watching other pictures and other actor's work. On one stage they were shooting a picture called Blackmail, the first all-talking film to be made in England. It starred Anny Ondra, who is now Mrs. Max Schmeling, and Donald Calthrop, the erratic one.

As I was watching the stunning Anny Ondra, hardly daring to blink my eyes in case I missed any move she might make, I was approached by an egg-shaped individual with a pontifical manner, who bowed with a slow seventeenth-century grace and said, "I am the director of this phantasmagoria and my name is Alfred Hitchcock." He pronounced it as if it were two words—Hitch Cock. One of the gay spots in those days was a place called Skindles on the Thames at Maidenhead, about twenty miles southwest of London. It was the setting for strange, very chic mesalliances. One could have an excellent lunch in the garden at the edge of the river.

Strangely enough, I wasn't thinking of Hollywood. I was seeing New Mexico and Arizona and the Utah of Zane Grey and the far Pacific. When I came to, I was standing outside the Empire Theatre in Leicester Square, the MGM showcase. I don't remember the name of the picture, only that Charles Bickford and Kay Johnson were playing in it. I went in and sat through it twice. I devoured every tree, every street, every set, and every face. I kept marveling at the prospect that I could be seeing these very places and people in a matter of weeks. Could this be happening to Reggie? Suddenly I was very tired and saw that it was almost midnight, and I wanted to go home and dream and be alone.

There was a large bed facing us and in the middle of it was a tiny little woman who looked like a gnome. She had short cropped hair that looked ragged and alert black eyes with very dark shadows under them. She looked ill. She had a bottle of some black liquid in her hand, and on the nightstand stood almost a dozen more. Ah, I thought, a dope fiend of some kind. Robert Lisman (a talent scout who worked for MGM) introduced me and said, "And this is Anita Loos, who is going to help us." Miss Loos was a successful author, known for her play, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. She looked at me very clinically and said, "How are you? Have a Coke." I shook my head. "No, thank you, Miss Loos." I wasn't going to touch that stuff!

I went down to the dining room at Hotel Plaza, ordered a seafood salad and a tall whiskey and soda. The waiter said he could get me the salad but the whiskey was out. I asked him why. He replied, "I don't know where you've been, sir, but this is the United States and we have a thing here called Prohibition." I discovered a compensation. Chocolate malted milk! So thick you almost had to eat it with a spoon. MGM kept me in New York for five days, and during that time I saw two shows and a dress rehearsal. One was George White's Scandals, in which I was fortunate enough to see three of the funniest performers of this or any other time, Jack Benny, Phil Baker, and Patsy Kelly. The other was a rather dull play, but with a wonderful actress, Laura Hope Crews. The third one was a dress rehearsal of The Warriors Husband. The leads were played by Franchot Tone and Katharine Hepburn. I boarded the Twentieth Century for my journey to California, and frankly, I wasn't sorry to leave New York. To me, New York was not an attractive city and it is even less so now.

With the exception of the Plaza Hotel and a few other buildings, since torn down, I thought it angular and dingy, with the dinginess of squalor, not age. Admittedly, it was just after the big stock market crash and the Depression was setting in, but I've paid hundreds of visits since and the city hasn't improved. Quite the opposite. That night I caught the Chief for Los Angeles. The next morning I began to get a little worried. Where were the lands that Clarence E. Mulford had promised me? The lonely plains and quiet rivers of James Fenimore Cooper? Later that day I began to feel easier. The country began subtly to change. Great vistas started appearing, tawny deserts. Far in the distance one could sense mountains, and suddenly there was Gallup, New Mexico. And Albuquerque and my first real Indians in all their regalia, sitting on the bricks of the railway station. I bought a silver and turquoise brooch from one of them to send to Aunt Luisa. My America really did exist.

Then came the cactus and the Joshua trees, the deserts and orange groves of California and, before I was ready for it, Los Angeles. It was a bright and sunny Saturday morning and already very hot. As I stepped off the train I was approached by an exquisitely dressed young man who inquired, "Are you Mr. Milland?" I nodded and he introduced himself. "My name is Jerrold Asher and I'm in the publicity department of MGM. I'm supposed to look after you and see you settled in your hotel. We've got a room for you at the Ambassador for a week, but after that I'm afraid you'll be on your own. Ever been in America before? No? Well, don't worry about it. I'm always at the end of a phone and I'll be glad to help any way I can." With that, we collected my luggage and climbed into a huge limousine and drove off. We finally arrived at the Ambassador, which, for those days, was an amazing place.

Huge gardens, swimming pools, restaurants, and of course, the famous Cocoanut Grove. Asher turned out to be a delightful character who seemed to enjoy a pose of bitter disillusion. He knew everyone, it seemed. But when his ashes were put away thirty-eight years later only my wife and his brother-in-law were there. Before he left he told me that Robert Lisman, the MGM talent scout, who had arrived the day before, would be picking me up at six o'clock that evening together with a Mr. and Mrs. Rohde, who were writers. We would have dinner at the Brown Derby and then go on to a premiere at the Pantages Theatre. When he left I went downstairs to the coffee shop and had a chocolatemalted milk. It was even thicker than the ones in New York. I saw people at the Brown Derby whom I had never really believed existed. There was Tom Mix, dressed in white leather, and much shorter than I expected.

There was the flashing, beautifully dressed Joan Crawford, the gross-looking, shambling Wallace Beery, the breathlessly lovely Corinne Griffith, and a rather common-looking girl with platinum hair and a surly expression, which was just about all she wore, who turned out to be Jean Harlow. And then my evening was made, for, with a joyful smile and rollicking walk, in came Victor McLaglen. I got my first apartment in a court on Hayworth just below Sunset called The Inglaterra. Living room, bedroom, bath, and kitchen completely furnished, telephone, and weekly maid service all for forty dollars a month. Oh, the phone was four and a half dollars a month extra. Ah, those olden, golden days!

The first time I stood in front of a camera in Hollywood happened the following week. It was a test for Cecil B. De Mille, who was preparing The Squaw Man. It was also a first for the man who directed my test, a young set designer for De Mille named Mitchell Leisen. I don't know which of us was the more nervous, but I think Leisen had the edge. Most of the extras dressed better than the stars, and it was always possible to be noticed and picked out of the crowd and given a special bit. A lot of stars started that way. But those days are gone now. You've got to belong to the right union. I met a most attractive girl who was taking lessons from an Austrian instructor. You know, it's a strange thing when a foreigner first comes to the States. He is struck by the fact that some Americans speak more attractively than others. To a foreigner, they all speak exactly the same language. But some are pleasanter to listen to. And this gal was pleasant indeed. All aspects of her. She also had a wicked sense of humor. We went out dancing on Saturday night and went swimming on Sunday at Malibu. There was only one thing wrong with her. I'll call her Bernadette Conklin, which was not her real name. She lived in Glendale. I defy any stranger to find his way back from Glendale to Hayworth and Fountain at one o'clock in the morning, and I was no exception. I got lost every time.

There was a peculiar contractual distinction in the studios in those days. If you were earning a hundred dollars a week or less, you were a "stock" player and therefore could be called upon to do all kinds of publicity gimmicks, go to all the openings, whether they were of outhouses, department stores, or gas stations, and you had to attend drama school. Over a hundred dollars a week and you were a "contract" player and were more or less immune to that sort of thing.

I had picked a scene from a picture called Passion Flower, soon to be made with Kay Francis and Robert Montgomery. To work with me they had assigned the cutest, prettiest little Dresden doll I had ever seen. Her name was Mary Carlisle and she was about as big as a bar of soap but luckily she had a great sense of humor. At the end of the rehearsal she said to me, "I thought you were English." "I am," I said, "but in this scene I'm supposed to be an American. Don't you think I sound like one?" "Oh," she said, "you do, you do. Yes, indeedy." When it came time for Mary and me to do our little scene, which was only three pages long, somebody obviously had left the key open, because all the way through it I kept hearing giggles and chuckles and at the end roars of laughter. One bastard was actually lying on the floor. It wasn't supposed to be a funny scene. It turned out that Miss Bernadette Conklin came from a place called Pineapple, Alabama, and I had acquired the damnedest Southern accent ever heard north of the Panama Canal. Curtain. Two weeks later I was given my first legitimate part.

It was in a picture called Bachelor Father, and it starred Marion Davies and the Englishman C. Aubrey Smith. The movie was directed by an elephantine gentleman named Robert Leonard, who immediately restored my faith in American directors. He was well-mannered and patient and very much respected. The film was produced by Cosmopolitan Pictures (owned by W. R. Hearst) and released through MGM. Before the actual shooting began it was decided that we should all go up to "the ranch" to rehearse for two weeks.

This meant San Simeon, the Camelot of California. Suddenly I felt very lonely, and nostalgia came again, only this time it was more insistent. Pedants have said it is a childish emotion that should have no place in a mature mind. If this is so, then I am a child still. It is always with me and will be until I die. I had met Rex Ross through Jerry Asher. We were waiting around on the set of Bachelor Father. Rex was one of the first friends I made in Hollywood and he has remained so. Today he is one of the most respected surgeons in California and lives just down the road from me. We arrived at the MacLeod house in Pasadena. It was a large, stone, Provençal-style house just off Colorado Boulevard with a courtyard in front and a tennis court and pool down to the right. I seated myself at the end of a foundered couch, next to an extraordinary-looking girl.

Round face, red hair, heavy pouting lips, and a black eye. And when I say a black eye I mean a shiner. She was dressed all in white and was feeling no pain at all. I had met my first real Hollywood star. She was Clara Bow. She scrutinized me for a moment or two and then said, "Hi, don't drink the Scotch, it will kill you. Take the gin. It might not." I asked her who was the fellow with Clara Bow. She said he was a well-known leading man named James Hall, and would I go back to the bar and get two more drinks. It was about fifteen minutes later, when the ice was beginning to rattle, that Miss Bow, who was beginning to get bellicose, suddenly banged Mr. Hall right smack in the beezer and charged out of the front door. It was in the middle of these two drinks that I suddenly began to feel very, very floaty. I knew I had to make a choice; either throw up or die. So I bolted for the door with Janet after me. I just made it, and when I got through I still wanted to die. Janet insisted that I should not drive home, and I insisted that I should and that I would meet her at Flintridge Riding Academy at seven thirty Sunday morning as arranged. Somehow I got home and, after throwing up again, went to sleep. As a matter of fact, it was many months before I took another drink. Very chastening.

I had gone to a late brunch and bridge party in Beverly Hills. The house was huge, part of a compound of four and all owned by a crusty little millionaire named J. J. Murdock. The story was that he'd had a tunnel built under all four of them, the other three being occupied by his executives and their families, and that he had had listening devices installed. Sounded like Nightmare Park. I had tagged along with Janet and a girl named Martha Sleeper, who happened to be Murdoch's niece. I felt a touch on my shoulder, and it was Janet with another girl in tow, to whom I was introduced. I never heard her name because my world suddenly stood still and I felt completely lost. The room was empty and there was just her, tall, with dark hair with some silver in it and eyes that were truly sapphire. Her expression was gently humorous while I mumbled some garbled inanities. I was still doing it even after they moved on. I dropped into my seat with a thud, looking and feeling very odd. The fellow on my right, Johnny Truyens, asked if I felt all right. Could he get me something? I said no, it was just that I had forgotten something and I had to get to a phone right away. And with that I left the room. I was bemused and felt the tiniest touch of panic.

Up until now I had never felt any really deep emotion; no one had ever touched me inside. I had been self-sufficient or, more correctly, self-centered and solitary. Suddenly I had met someone I wanted terribly to impress and I didn't even know her name. I had to get hold of Janet and, without arousing her suspicions, find out who she was and all about her. I set about my plan with all the deviousness of someone trying to sell a farm, with the result that at the end of the following week, after our early-morning session at Flintridge, Janet announced that she was taking me to breakfast in a house in Hollywood. Where I lived in Hollywood in those days was a most intriguing area. It was an area made up of big old California houses of stucco and wood, Victorian monstrosities straight out of Ronald Searle, trashy little Mexican apartment courts, and the most beautiful apartment houses ever designed.

Places like La Ronda, Andalusia, the Garden of Allah, none of which could be built now. Because elegance and taste and artistry seem to have died. People today are forced to live in the obscene chicken coops that have taken their place. But in those days Carole Lombard lived there, and Ernest Torrence, Allan Dwan and Gloria Swanson. And often in the still, early hours of the morning one could see tortured and pallid writers slowly plodding under the trees sweating out scenes for Black Oxen or Greed. I asked if I could call her and perhaps drop around some evening, since I lived only a block away. She supposed that would be all right; I could always get her number from Janet.

Now I don't propose to go into the long and troubled story of my courtship. I had been kissed by the angels and that there must have been something good in me to have been able to recognize the good in her. It took almost two weeks to get her to agree to go to the movies with me. Her reluctance had something to do with the fact that Janet was her good friend and also because she was attending USC. So Friday night was the only night available. Eight months later we were married at the Riverside Mission Inn. There were two hundred and fifty guests and three rehearsals. At what I thought was the last rehearsal, when we got to the part where the groom is supposed to kiss the bride, I didn't, whereupon my lovely bride hissed, "Kiss me. Kiss me!" I said, "No, let's wait for the real thing." She whispered, "This is the real thing!" I almost fainted, and then kissed her. During that eight-month campaign I appeared in three pictures. Two on loan to Warner Brothers, and one at MGM.

But the only one worth any comment was a picture called The Man Who Played God. I played a very small part in it, and the film itself was easily forgettable. But it gave me the opportunity to watch a true professional at work, a man completely dedicated to his trade, a man of immaculate good manners. He was George Arliss, and at that time probably in his sixties. He was a small man, thin, with bony features and a slight cast in one eye. The part of his protegee, a young girl, was played by Bette Davis, in those days a very pretty and pleasant creature, given to sitting at people's feet in rapt attention. No sign of her later arrogance and imperiousness. I suppose I must have been adequate in the small part I had been given, because Warner Brothers borrowed me again four months later for a slightly better part in a film starring Jimmy Cagney and Joan Blondell called Blonde Crazy.

One thing I do remember, though, was Cagney's lousy piano playing. Several years later I asked him if he had ever finished his mail-order course of piano lessons. "Nah," he replied, "the goddam neighbors got a court order and I had to send the piano back." We got to know each other quite well over the years. He and his brother Bill could have been twins except for temperament—Bill being ebullient and gregarious where Jimmy was something of a loner. Our friendship was based upon our mutual love of boats. We never talked about the theatrical world, just boats. We knew the faults and shortcomings of every boat from San Francisco to San Diego together with the faults and perversions of their owners. At one time Jimmy owned a small and lovely old Gloucester schooner called the Martha and I was the proud owner of a Sparkman and Stephens yawl called the Santana. About two weeks before I got married a small incident occurred which almost nipped my career in the bud.

I had been cast in another picture with Marion Davies called Polly of the Circus and as I mentioned earlier her leading man was Clark Gable. At that time Gable was just making his mark as something new on the Hollywood horizon, a leading man who did not conform to the pattern, big, tough, and with a calculated disrespect for women. Well, for him it worked. I don't remember what sort of character he played in the movie, but I had been cast as a young gym instructor in a boys' club. He was supposed to visit the club and put on a boxing exhibition for the benefit of the boys and I was the goat. It was just a thirtysecond scene and quite well rehearsed. One of my instructions was not to hit him in the face.

He was big and very strong and outweighed me by about thirty pounds. But he was just a little bit slow, and he wore a partial bridge in the upper left side of his mouth. About halfway through the scene he stuck a straight left in my ear and I countered with one of my own, purely reflexive, done without thinking—and out popped the bridge, only to fall right under my foot. From that day on Gable never really trusted me, although we met two or three times a month at different parties over the next thirty years. We also belonged to the same golf club and played in foursomes together dozens of times, but he would never take me as a partner, there was always that touch of suspicion.